‘Damuroxó-a Mestre dos Bordados’

is the result of research done in Sacatar, an AIR in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil. This film is an attempt to define the movements and metamorphose of ‘cultural’ identity. How has it been passed down to the next generations? How has it survived the tension of assimilation and still kept the essence of its source? The underlying topic of “Damuroxó’ is the evolution of a skill; how a craft, a detail of a cultural identity, has transcended borders and races and developed throughout time, becoming a new and powerful language in another culture.

- Project:

- The Learning Hand

Embroidery as a visual language

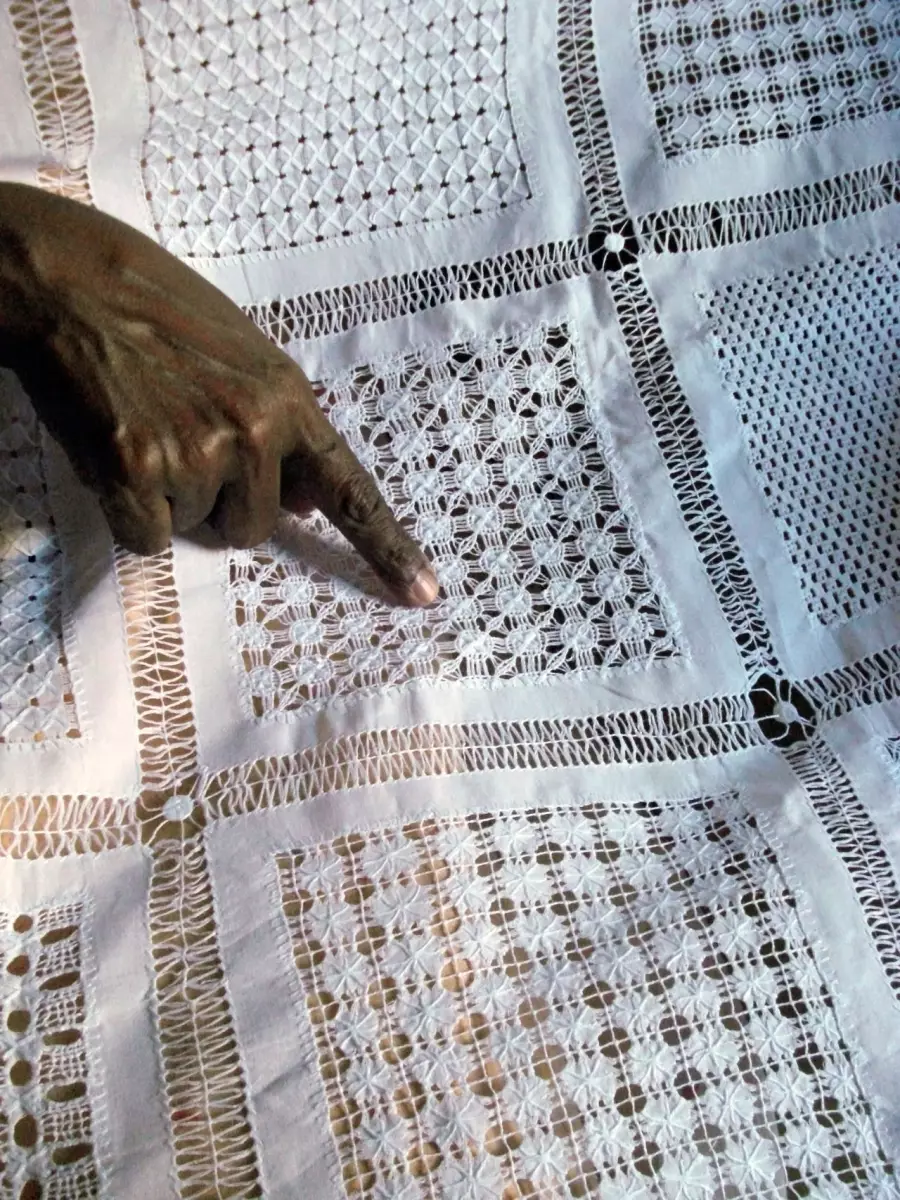

The protagonist is Mãe Itana a master of embroidery, but above all she is a high priestess of the Candomblé religion. Candomblé is an example of religious ‘hybridization’: a mix of Catholicism and the voodoo religions of Western Africa. During the slavery era, Africans were obliged to give up their beliefs and convert to Christianity. They found intelligent ways to disguise their practices making it look like Catholic rituals but keeping within it the characteristics of their gods. Part of the Candomblé rituals is the complex embroidered clothing of its priestesses. The patterns and stitches are closely related to specific gods and the levels of seven years of initiation. They are used within very specific rules, giving the embroidery a symbolic meaning. Consequently the embroidery functions as a visual language.

When the Candomblé priestesses parade in their costumes everyone knows which goddess is represented and their place in the hierarchy of the cult; the more intricate the pattern, the higher their position is. Urânia Munzanzu, the apprentice of Mãe Itana, shows in the film the different pieces of the costume. She proudly sums up with the words: ‘What you see is power!’

This craft is a visual language and above all, it is a powerful and living expression of a new cultural identity.

For the origins of this craft we have to go back 500 years when the Portuguese colonists brought these skills to Brazil. The majority of these embroidery stitches can be directly linked to specific villages or islands in Portugal. Although the roots lay in Europe the skills here have nearly been lost. In the Candomblé embroidery, we are still able to recognize the source but is has, in time, been appropriated, transformed and extended. The urgency of this work is to reflect on the cross-cultural relations.

As an artist I am fascinated by the fact that this craft is the embodiment of a cultural shift. From a decorative handwork made exclusively by the white colonizers it passed secretly to the undergarments of women slaves. When they became free they wore these clothes exhibiting their embroidery skills, demanding attention and appreciation. This craft is a visual language and above all, it is a powerful and living expression of a new cultural identity.